Doctoral research

PhD, Royal Academy of Music, London

Introduction

I discovered the violin at the age of seven when I went with my primary school to see an exhibit of Stradivaris (it was, I discovered much later, the famous Axelrod collection). As soon as I heard these incredible violins I was hooked. More than anything, it was the sound itself that fascinated me. I soon became obsessed with violinists such as Fritz Kreisler, Mischa Elman, and Jascha Heifetz - especially Heifetz’s early recordings of Sibleius, Tchaikovsky, and Glazunov Concertos (my favourite CD for many years). The apparently limitless variegation of nuance and colour, and the deep emotional fervour in this kind of playing fueled an interest in what I would now call an ‘ideal violin sound.’ In light of this concept, I have devoted myself to studying the practices and traditions from which these kinds of sounds developed. There seems to be a conventional acceptance that the technical level of violin playing has never been higher than it is today.[1] However, how we conceive of violin sound, the nature of the ‘ideal sound’, and the technical means by which violinists produce this sound have changed dramatically over the last century.[2]

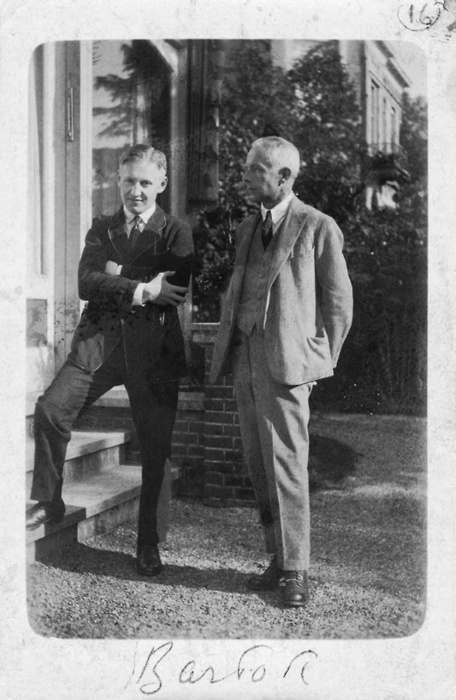

This thesis was motivated in part by a desire to situate the evolution of these changes in the context of my own playing. I was drawn to Bartók’s violin works, and especially to his First Sonata for violin and piano (1921), because it was written at a time when violin playing was changing significantly. Bartók was immersed in a world where both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ traditions of violin playing impacted profoundly on his violinist-collaborators. Using Bartók’s First Violin Sonata as a point of focus, I consider broader questions of musical language, advanced learning, and something T.S. Eliot calls an artist’s “historical sense” as they are involved in my engagement with musical tradition. I explore the sound-world in which Bartók operated and the key violinists with whom he worked. I explore the nature of advanced learning and examine my own engagement with three eminent violinists connected to the Hungarian tradition, and thus connected to Bartók’s collaborators. These one-to-one sessions provide a wealth of material through which I begin to see elements of a musical language taking shape. Over the course of my research, I recorded Bartók’s First Sonata four times. These recordings chart the changes in my performances over a four-year immersion in this particular musical dialect.

My immersion in the Hungarian tradition dates back to my undergraduate studies in Manchester. Before university my primary violin teacher was Atis Bankas (pupil of Semyon Snitkovsky in Moscow, who was a pupil and assistant to David Oistrakh). I was first exposed to the Hungarian tradition in 2005, when I joined the studio of Yair Kless (pupil of André Gertler, who studied with Jenő Hubay, and a pupil of Ivan Galamian). Then in 2009 I began studying with György Pauk (pupil of Ede Zathureczky, who also studied with Hubay). Kless and Pauk, though they were both taught by Hubay pupils, play and teach in very different styles. Moreover, they do not seem to share a common vision of what constitutes an ‘ideal violin sound’ or an ideal musical interpretation. These differences raised questions in my mind about just what it is to be part of a musical tradition. How and to what extent do our teachers influence our approach to sound and musicianship? How can I, as a musician with a strong sense of individuality, relate to a tradition? Indeed, more generally, we need to ask what is a tradition? And is there always a conflict between individual musical expression and participation in a musical tradition?

(read more by clicking on the link below)

[1] Defining ‘technique’ is problematic; provisionally, let me stipulate it as facility, accuracy of intonation, smoothness of bowing, and reliability on stage.

[2] For an example of this conventionally held belief, see appendix B for the transcript of the discussion between Pauk and László Somfai, recorded July 2011 at the Bartók Festival and Seminar in Szombathely, Hungary.

This thesis was motivated in part by a desire to situate the evolution of these changes in the context of my own playing. I was drawn to Bartók’s violin works, and especially to his First Sonata for violin and piano (1921), because it was written at a time when violin playing was changing significantly. Bartók was immersed in a world where both the ‘old’ and ‘new’ traditions of violin playing impacted profoundly on his violinist-collaborators. Using Bartók’s First Violin Sonata as a point of focus, I consider broader questions of musical language, advanced learning, and something T.S. Eliot calls an artist’s “historical sense” as they are involved in my engagement with musical tradition. I explore the sound-world in which Bartók operated and the key violinists with whom he worked. I explore the nature of advanced learning and examine my own engagement with three eminent violinists connected to the Hungarian tradition, and thus connected to Bartók’s collaborators. These one-to-one sessions provide a wealth of material through which I begin to see elements of a musical language taking shape. Over the course of my research, I recorded Bartók’s First Sonata four times. These recordings chart the changes in my performances over a four-year immersion in this particular musical dialect.

My immersion in the Hungarian tradition dates back to my undergraduate studies in Manchester. Before university my primary violin teacher was Atis Bankas (pupil of Semyon Snitkovsky in Moscow, who was a pupil and assistant to David Oistrakh). I was first exposed to the Hungarian tradition in 2005, when I joined the studio of Yair Kless (pupil of André Gertler, who studied with Jenő Hubay, and a pupil of Ivan Galamian). Then in 2009 I began studying with György Pauk (pupil of Ede Zathureczky, who also studied with Hubay). Kless and Pauk, though they were both taught by Hubay pupils, play and teach in very different styles. Moreover, they do not seem to share a common vision of what constitutes an ‘ideal violin sound’ or an ideal musical interpretation. These differences raised questions in my mind about just what it is to be part of a musical tradition. How and to what extent do our teachers influence our approach to sound and musicianship? How can I, as a musician with a strong sense of individuality, relate to a tradition? Indeed, more generally, we need to ask what is a tradition? And is there always a conflict between individual musical expression and participation in a musical tradition?

(read more by clicking on the link below)

[1] Defining ‘technique’ is problematic; provisionally, let me stipulate it as facility, accuracy of intonation, smoothness of bowing, and reliability on stage.

[2] For an example of this conventionally held belief, see appendix B for the transcript of the discussion between Pauk and László Somfai, recorded July 2011 at the Bartók Festival and Seminar in Szombathely, Hungary.

Abstract

My work on Bartók’s First Sonata functions as a case study of the kind of engagement implicit in what T. S. Eliot calls an artist’s ‘historical sense’. I develop an interpretation of the work over the period of research. To this end, I approach the sonata from three angles: (1) a close study of the violinst-collaborators of the Hungarian school who played a formative role in the composition of the work (Jelly d’Aranyi, Joseph Szigeti, and Zoltán Székely); (2) study of the treatises that informed the violin playing of the time of its composition, especially within the Hungarian school; and (3) video-recorded and analysed sessions with three mentors who represent this tradition in its current state (György Pauk, Yair Kless, and András Keller). I recorded Bartók’s First Sonata four times as a means to chart the evolution of my own performance practices.

(1) As a pianist, Bartók’s conception of string sound was not borne of the kind of intimate experience of a professionally trained string player. Nevertheless, close friendships and working relationships with a number of violinists helped him to better understand the mechanics, and more importantly the distinct sound-world, of violin playing. In this regard, Bartók’s conception embodies the spirit of violin playing from the early part of the twentieth century. My guiding hypothesis here is that the technique, sound, and musicianship of Bartók’s key violinist-collaborators are constitutive elements of the musical dialect of Bartók’s violin works.

(2) The evolution of violin playing in Bartók’s lifetime was quite dramatic, and these changes are reflected in the treatises written by several practicing violinists, in particular Joseph Joachim, Joseph Szigeti, and Carl Flesch.

(3) I consulted with Pauk, Kless, and Keller not simply to unearth historical performance details. I also use the music as a focal point for broader questions about musical language, technique and interpretation.